14 JUN 1991 PUNJAB DECLARED DISTURBED AREA

II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The Sikh religion was founded in India by Guru Nanak (1469-1539), a mystic poet who rejected both Islam and Hinduism, yet drew on elements of both to construct a monotheistic religion that teaches escape from rebirth through devotion and discipline. Sikhism arose at the time of the height of power of the Mughal Empire in India (1526-1757). Wary of the growing power of the Sikhs, the Mughals took brutal steps to suppress them, executing their leaders and creating a tradition of militancy and martyrdom that resonates in contemporary Sikh politics.10 A short-lived Sikh empire was destroyed in 1849 after two wars with the forces of the British East India Company. The British army was so impressed with the fighting skills of the Sikhs, however, that they subsequently inducted hundreds of Sikh soldiers to serve with the British forces in India. After India gained independence in 1947, Sikhs continued to figure prominently in the military.11 10 For more on the history of the Sikhs in Punjab, see generally, Robin Jeffrey, What's Happening to India? (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1986); Kuldip Nayar and Khushwant Singh, Tragedy of Punjab (Delhi: Vision Books, 1984); Mark Tully and Satish Jacob, Amritsar: Mrs. Gandhi's Last Battle (London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1985). 11 The recruitment of Sikhs grew after the "Indian Mutiny" of 1857, when Hindu and Muslim soldiers rebelled against their British officers in several cities in North India. In the uprising, Sikh soldiers remained loyal to the British forces and were rewarded with prominent positions in the military. Although Sikhs comprised only 2 percent of the population, they made up some 20 percent of the imperial army. That special status was threatened in 1980 when the Congress (I) government introduced state quotas which reduced the Sikh presence in the army from 15 percent to 6 percent. See Lloyd Rudolph, "India and the Punjab: A Fragile Peace," The Asia Society Asian Agenda Report (Lanham, MD: 12 University Press of America, 1986), pp. 33-53, p. 40. 13 Sikhs played a leading role in the independence struggle, and the experience fostered efforts within the community to promote Sikh identity and culture. During that time, a committee known as the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) was formed to oversee the management of the Sikhs' most important temple, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and other historical gurdwaras ("temples") in Punjab. This coincided with a successful campaign by a Sikh political party, the Akali Dal,12 to take back control of the gurdwaras from non-orthodox Sikhs supported by the British. Ever since, the SGPC has played a critical role in Sikh politics.13 The partition of British India that created the independent nations of Pakistan and India in August 1947 drew a line through Punjab and through the Sikh population. When the resultant civil conflicts and migrations ended, the Sikhs were 12 The party drew most of its support from Jat Sikhs, a powerful agrarian caste. In theory Sikhism does not recognize caste, but in practice caste identities are still meaningful and divisive. Not all Sikhs are Jats, and the Congress (I) party has traditionally drawn support from other Sikh communities in Punjab. As Lloyd Rudolph notes, "Sikh power in Punjab is problematic in part because Sikhs are a bare majority, in part because Sikhs, divided as they are by interest, class and ideology, cannot easily be represented by one party.... One consequence of these considerations has been that the Congress Party has won more Sikh votes than the Akali Dal party in most of Punjab's elections." Ibid, pp. 49-50. 13 "[The SGPC] developed into a kind of Sikh parliament, with control over temples in the Punjab and their huge annual incomes." Tully and Jacob, p. 31. 14 concentrated in India in east Punjab, where they made up 35 percent of the population.14 In 1953, India's central government appointed a commission which redrew the boundaries of all the states, with the exception of Punjab, along linguistic lines. In response, Sikh leaders mobilized for a Punjabi language-majority state which would have included most Sikhs.15 Fearing that a Punjabi state might lead to a separatist Sikh movement, the central government opposed the demand. In response, Sikh politicians launched a civil disobedience campaign that led to the arrest of thousands by the end of 1955. Continuing civil disobedience campaigns precipitated the arrest of over 50,000 Sikhs between 1960 and 1961. 14 Jeffrey, p. 32. 15 Most, but not all, Sikhs speak Punjabi. Many Hindus also speak Punjabi, as well as Hindi. Because the Indian constitution discourages demands by minority groups on the basis of religion, language issues have been used to assert ethnic group interests. A campaign by Hindu Punjabi leaders, including Lala Jagat Narain, the editor of the Hind Samochar newspaper chain, to persuade Hindus in the state to record their language as Hindi -- and not Punjabi -- during the census embittered Punjabi Sikhs. Many Sikhs also considered the government's refusal to reorganize Punjab along linguistic lines discriminatory toward Punjab, and Sikhs in particular. 15 In 1966 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi agreed to divide Punjab along linguistic lines into the states of Punjab and Haryana.16 Chandigarh17 was to serve both Punjab and Haryana as a joint capital under central government protection and administrative control. But after further negotiations, Prime Minister Gandhi acceded to Sikh demands to award Chandigarh to Punjab, although the transfer was never implemented. In October 1978, the Akali Dal adopted 12 resolutions which came to be known collectively as the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. In addition to propagation of the Sikh faith, the resolution called for "creation of such an environment where Sikh sentiment can find its full expression" and demanded the transfer of Chandigarh and other neighboring "Punjabi speaking areas" to Punjab.18 16 However, the division left several Punjabi-speaking areas out of Punjab. Their inclusion in the state became one of the demands of the Akali Dal. 17 The new capital designed by French architect Le Corbusier in 1953. 18 The resolution was drafted by a working party of the Akali Dal in 1973; the 1978 conference formally endorsed a package of principles which came to be known as the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. According to it, Punjab was to have direct control over all departments of government, restricting central intervention only to defense, foreign affairs, communications, currency and railways. Rival factions within the Sikh community promoted different interpretations of the implications of the resolution, varying from the extremists' seeing in it a call for a separate Sikh nation of Khalistan, to the moderates, who sought greater state autonomy for Punjab within India's federal union. See Jeffrey, pp. 158-159; Tully and Jacob, pp. 50-51. 16 When Prime Minister Gandhi declared a state of emergency on June 26, 1975 -- suspending fundamental rights, imposing press censorship and arresting hundreds of opposition party leaders -- Sikhs were among her most outspoken critics.19 Thousands of Akali Dal members were imprisoned during the two years of the Emergency. When the government ended the Emergency and called for a general election in 1977, the united opposition, the Janata Dal, won by an overwhelming majority. In the state elections in Punjab, the Congress Party20 was defeated, and an Akali Dal-Janata Dal administration came to power. Factional rivalries within the opposition alliance and its failure to restore credibility to the central government were sufficient to impel Indian voters to reelect Indira Gandhi by a wide margin in 1980. Her government then dismissed nine state legislatures, including the legislature in Punjab. Local state elections were held in May 1980, and the Congress Party was returned to power in Punjab by a narrow majority. In the aftermath of local elections, extremist Sikhs grew bolder, openly courting confrontation with authorities. On September 9, 1981, Lala Jagat Narain, the leading Hindu journalist and publisher, was assassinated near the city of Ludhiana in Punjab.21 The followers of Sant Bhindranwale, a fundamentalist preacher who had been courted by Congress (I) leaders hoping to use him to discredit Sikh opposition party leaders of the Akali Dal, were suspected. On September 20, Bhindranwale, who had eluded police since the murder, made a dramatic surrender before a crowd of 200,000 supporters and politicians. His arrest precipitated riots; 25 days later, he was released. 19 "Agitational politics are endemic in Punjab, used by the leading non-Congress party there, the Akali Dal, to mobilize support when it is out of power. It is especially significant to note in this context that the only sustained agitational movement against the Emergency regime was carried out by the Akali Dal during those years." Paul R. Brass, "Punjab Crisis and Unity of India," India's Democracy: An Analysis of Changing State-Society Relations, Atul Kohli, ed., (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), pp. 169-213, p. 176. (author's emphasis). 20 The Indian National Congress has dominated Indian politics since its founding in 1885, providing the organization and leadership behind India's independence movement. Since 1969, the party has suffered a number of schisms; however, the Congress Party (I), for Indira Gandhi, dominated all rival parties. The Congress Party (and the Congress Party (I) after 1969) has won every election since independence except two. After Indira Gandhi's assassination, the party was led by her son, Rajiv Gandhi, who was prime minister from 1984-1989. His assassination on May 21, 1991, ended the Nehru-Gandhi family's control of the party, leaving no clear successor. 21 See footnote 14, 15. 17 With the events of September 1981 came a marked increase in random attacks on civilians in markets and other public places. Bhindranwale's followers hijacked an Indian Airlines plane and assassinated Hindu and moderate Sikh politicians and policemen. Bhindranwale's few weeks in jail only increased his popularity; by the year's end he was the unchallenged leader of the Sikh extremists and arguably the most powerful leader in Punjab. The years between Bhindranwale's arrest in 1981 and the Indian army's assault on the Golden Temple in Amritsar in June of 1984 were marked by protracted negotiations between the Gandhi government and the Sikh Akali Dal leadership. After 1982, the Akali Dal demanded the implementation of the Anandpur Sahib resolution, including more autonomy for the state, the promised transfer of the capital city Chandigarh and other Punjabi-speaking areas to Punjab, a Sikh code of personal law,22 quotas for Sikhs in the military, and the deletion of language in the Indian constitution which brackets Sikhs with Hindus.23 Control over local river waters represents the key to prosperity for the farmers of Punjab, and the Akali demands also included a more equitable share of the water from local rivers -- a demand that was bitterly opposed in the neighboring state of Haryana.24 In April 1982, Prime Minister Gandhi announced construction of a canal to provide more of this water to the states of Haryana and Rajasthan. In response, the Akali Dal launched another civil disobedience campaign, hoping to enlist the support of Hindu farmers in Punjab in their efforts.25 Sikh extremists, however, took another tack. On April 26, two severed cows' heads26 were placed in a Hindu temple in Amritsar, provoking riots in several cities. The Dal Khalsa, or "army of the pure",27 was believed responsible.28 22 The Indian constitution recognizes separate legal codes governing family law for Muslims, Hindus and Christians. 23 Sikhs claim that this treatment wrongly implies that they are a sect of Hinduism. See Jeffrey, p. 158. 24 Punjab's abundant water supply contributed to the success of "Green Revolution" farming methods which introduced new high-yielding hybrid seeds on a large scale in the state. As a result, Punjab became India's most prosperous agricultural state. 25 Jeffrey, p. 161. 26 Since the cow is sacred to Hindus, the act was a sacrilege, designed to provoke a riot. 27 The name of the Sikh army founded in the 1730s to fight the Mughals. 28 See Jeffrey, p. 162. According to Asia Watch sources, the shadowy group was believed to have the backing of Congress (I) Home Minister Zail Singh. 18 On May 1, 1982, the government of India broke off talks with the Akali Dal and banned several Sikh organizations, including the Dal Khalsa. Members of the banned organizations retreated to the Golden Temple complex, essentially a small walled city. By May 1982, it had become Bhindranwale's headquarters, housing his armed followers and an arsenal of sophisticated weapons. On August 4, 1982, the Akali Dal launched another civil disobedience campaign, resulting in over 36,000 arrests in 88 days.29 Most of those arrested were released within a few days or weeks, but at least 2,500 Sikhs were held in preventive detention under the National Security Act.30 They were not released until after the conclusion of the Asian Games, held in Delhi from November 19 to December 4, 1982. Fearing disruption of the games, security forces in Haryana used roadblocks and searched cars and trains to prevent thousands of Sikhs from traveling to New Delhi. 29 Amnesty International, Report 1983, (London: Amnesty International, 1984), p. 195. 30 For more on the act and other security legislation, see discussion beginning on p. 148. 19 Talks between the Gandhi government and the Akali Dal resumed in late 1982 but ended in stalemate. The Gandhi government's concern for Congress Party victories in state elections that spring, and the continuing power struggle between the Akali Dal leaders and Bhindranwale's followers in Punjab undermined the negotiations. In addition, the failure of the civil disobedience campaigns to achieve a breakthrough prompted some politicians to align with the militants and justify the resort to violence. Attacks on policemen and civilians escalated. President's rule31 was imposed on Punjab on October 6, 1983, after a bus was ambushed and six Hindu passengers murdered. Increasingly, Sikh men were reported to have been executed in staged encounters32 with security forces, setting in place the cycle of violence that has dominated political life in Punjab ever since.33 In early 1984, the National Security Act was amended to permit detention without trial for up to two years for acts committed in Punjab or Chandigarh considered "prejudicial to the defense or security of the state." Hundreds of Sikhs were detained in the first months of 1984, including Akali Dal leaders arrested for burning copies of the Indian Constitution. On May 27, 1984, the Akali Dal announced plans to launch another civil disobedience campaign to begin on June 3, 1984. The president of the Akali Dal, Harchand Singh Longowal, threatened to halt 31 President's rule, or as it is commonly known, direct rule, is provided for under Article 356 of the Indian constitution. Under this article, the central government is empowered to dismiss an elected state legislature if the governor, a federal appointee, advises that "governance of the state cannot be carried out in accordance with the provisions of the constitution." The arbitrary manner in which president's rule has been invoked in Punjab and other states has led critics to observe that it has become a tool for purely partisan purposes. SeeLloyd Rudolph and Susanne Rudolph, In Pursuit of Lakshmi: The Political Economy of the Indian State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), pp. 101-102. Before the 1991 general elections, five states were under president's rule: Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Jammu and Kashmir, Assam and Haryana. 32 An "encounter killing" is the term used by police to imply that the victim was killed in a violent confrontation between government forces and armed combatants. In a great many cases, such encounters have been staged or have simply not occurred, and the term "encounter killing" has become synonymous with summary executions. For more on the practice, see discussion beginning on p. 38. 33 As Lloyd Rudolph has observed, "What brought the country to overt civil war ... was Mrs. Gandhi's increasing propensity to speak as if being a terrorist and being a Sikh were one and the same. She coupled this propensity with another, avoiding agreements with moderate Akali Dal leaders.... By [doing so] she strengthened Bhindranwale's hand, allowing him to capture the community's agenda and tactics. The politics of violence -- of terrorism, assassination and repressive state violence -- was allowed to replace the politics of electoral competition and policy bargaining." Rudolph, p. 42. 20 the sale of grain to the government's central reserves -- an act designed to threaten the government with higher food prices. On June 2, Prime Minister Gandhi announced over state-run All-India Radio that the army had been called into Punjab and that a curfew had been imposed on the entire state. Train service to Punjab was halted, foreign journalists were deported and domestic journalists were prohibited from reporting on the army action. The army, together with the Central Reserve Police Force, surrounded the Golden Temple complex. The army's full assault, code-named Operation Bluestar, began in the early hours of June 4 and ended on June 6.34 34 Although the army was not called out until June 2, firing broke out between the Central Reserve Police and Bhindranwale's forces on June 1. See Tully and Jacob, p. 144. 21 Because the area was closed to reporters and outside observers, it is difficult to assess civilian and military casualties in the battle. June 3 was a holy day for Sikhs, and thousands of pilgrims were housed along with temple employees within the Golden Temple complex. The government's White Paper on the Punjab Agitation gave official figures as 493 "civilians/terrorists" killed and 86 wounded, and 83 troops killed and 249 wounded.35 On October 27, the Indian press quoted official sources that put the total number killed (troops, militants and civilians) at about 1,000.36 Unofficial sources have estimated that the civilian casualties alone were much higher.37 35 Citizens for Democracy, Report to the Nation: Oppression in Punjab (New Delhi: Citizens for Democracy, 1985), p. 65. 36 Amnesty International, Report 1985 (London: Amnesty International, 1986), p. 210. 37 The fact that the bodies of those killed were cremated en masse by the army and police casts doubt on the government's figures. According to Tully and Jacob, more than 3,000 people were inside the temple when Operation Blue Star began, among them roughly 950 pilgrims, 380 priests and other temple employees and their families, 1,700 Akali Dal supporters, 500 followers of Bhindranwale and 150 members of other armed groups. "According to eye-witnesses about 250 people surrendered in the temple complex and 500 in the hostel complex after the two battles were over. The White Paper says that 493 people were killed and eighty-six injured. These figures leave at least 1,600 people unaccounted for. It would obviously be wrong to assume that they were killed in the battle, 22 The army apparently did not offer those inside the opportunity to surrender.38 A number of men captured by the army were summarily executed, and post-mortem examinations revealed that some had their hands tied behind their backs before they were shot.39 In one incident described by an eye-witness, but there must be a big question mark over the official figures of civilian casualties in the operation, a figure which is appallingly high anyhow for an operation conducted by an army against its own people." Tully and Jacob, p. 184-5. 38 See Tully and Jacob, p. 151. 39 Brahma Chellaney, a correspondent for the Associated Press, managed to stay in Amritsar after the rest of the foreign press and Indian journalists working for the foreign press had been deported from the city under police escort. He interviewed a doctor who conducted some of the post mortem examinations. See Kuldip Nayar and Khushwant Singh, Tragedy of Punjab (Delhi: Vision Books, 1984), pp. 165-166. See also, Tully and Jacob, pp. 170-172. Documents from two post mortem reports are included as appendices to the Citizens' for Democracy report, pp. 113-114. 23 [The detainees] were taken into a courtyard. The men were separated from the women.... When we were sitting there the army released 150 people from the basement. They were asked why they had not come out earlier. They said the door had been locked from the outside. They were asked to hold up their hands and then they were shot after fifteen minutes.40 Over 6,000 persons were detained following the assault, 800 of whom were released by June 27.41 For the next two months the army conducted largescale combing operations throughout the state, resulting in thousands of arrests. On October 31, 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi by two Sikh bodyguards. In the days that followed, anti-Sikh rioting paralyzed New Delhi, ultimately claiming at least 3,000 lives; unofficial estimates were higher.42 Sikh men were beaten, stabbed, and doused with kerosene and burned to death by mobs. In some neighborhoods, children were also killed, and women were raped. At least 50,000 people were displaced, and tens of thousands of Sikh homes and businesses burned to the ground.43 Sikhs were also attacked in other cities across northern India. Shortly after the riots, a fact-finding team organized by two Indian human rights organizations, the People's Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) and the People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), published a report on its investigation into the cause of the Delhi riots, Who Are the Guilty? The investigators concluded that the violence was the result of a "well-organised plan marked by acts of both deliberate commissions and omissions by important politicians of the Congress Party at the top and by authorities in the administration."44 Eyewitnesses confirmed that 40 Interview with Ranbir Kaur, an eyewitness to the assault, in Tully and Jacob, p. 171. 41 Amnesty International Report 1985, p. 210. 42 People's Union for Civil Liberties and People's Union for Democratic Rights, Who Are the Guilty? (New Delhi, 1984), p. 21. 43 Ibid. 44 Ibid, p. 1. 24 well-known Congress (I) leaders and workers ... led and directed the arsonists and that local cadres of the Congress (I) identified the Sikh houses and shops.... In the areas that were most affected ... the mobs were led by local Congress (I) politicians and hoodlums of that locality.45 Despite numerous credible eye-witness accounts that identified many of those involved in the violence, including police and politicians,46 in the months following the killings, the government sought no prosecutions or indictments of any persons, including officials, accused in any case of murder, rape or arson. A citizen's commission, led by former Chief Justice S. M. Sikri, appealed to the government to appoint an impartial tribunal to investigate the riots and identify those responsible. It was not until April 1985, however, that the government of India appointed Justice Ranganath Misra to head an inquiry. When the Misra Commission Report was released two years later, it recommended no criminal prosecution of any individual, and it cleared all high-level officials of directing the riots. In its findings, the commission did acknowledge that many of the victims testifying before it had received threats from local police. While the commission noted that there had been "widespread lapses" on the part of the police, it concluded that "the allegations before the commission about the conduct of the police are more of indifference and negligence during the riots than of any wrongful overt act." An additional committee established on the recommendation of the Misra Commission to examine whether registered cases had been properly investigated was declared null and void by the Delhi High Court in response to a petition by a Congress (I) member of Parliament who argued that no commission could be established outside the Commission of Inquiry Act. The efforts of a second committee to examine the role of the police in the killings were obstructed by government officials.47 In April 1987, the PUDR and the PUCL published a joint critique of the Misra Report, entitled Justice Denied. The authors noted: 45 Ibid, pp. 2-3. 46 These are listed in an annexure to Who Are the Guilty? pp. 38-45. 47 Harinder Baweja, "Blind Alley," India Today, January 31, 1990, p. 28. 25 The victims who volunteered to depose before the Commission found that in doing so they were faced with a renewed threat to their security arising from its peculiar procedures. It is significant that while the PUDR-PUCL report Who Are The Guilty? gave the names of the accused, but did not disclose the names of the victims who made the allegations, the Commission does the reverse. It is those who are held to be guilty who are anonymous while those who made the allegations are not only named but even their addresses have been published. And yet the number who courageously deposed before the Commission is significant. In Delhi alone they numbered more than 600. Having been failed by the Commission, where will they go now?48 In the national elections held in December 1984, the Congress Party won by a wide margin and Rajiv Gandhi became Prime Minister. In the months following Rajiv Gandhi's election victory, Punjab remained under president's rule. On July 24, 1985, Rajiv Gandhi and the Akali Dal leader, Sant Harchand Singh Longowal, signed an agreement granting many of the Sikh community's longstanding demands. The eleven-point accord promised compensation to the families of the victims of the 1984 Delhi riots and provided that Chandigarh would be transferred to Punjab on January 26, 1986. The accord further provided for a Supreme Court tribunal to adjudicate the dispute between Punjab and neighboring states over water rights and promised, somewhat vaguely, that the government would take steps to provide Punjab with greater autonomy. Less than one month later on August 20, Longowal was assassinated by Sikh extremists who regarded the accord as a compromise and a betrayal. In the Punjab legislature, a splinter party, the United Akali Dal, was launched to protest the accord and boycott state elections scheduled for the end of the year. With an unprecedented voter turnout, however, the Akali Dal swept the elections. The election appeared to signal widespread support for the accord in the Sikh community. Following the elections, Longowal's disciple, Surjit Singh Barnala, became chief minister of Punjab. 48 People's Union for Civil Liberties and People's Union for Democratic Rights, Justice Denied, (New Delhi, 1987) p. 16. 26 But the promised reforms did not take place. Threatened by angry protests from Hindu leaders in Haryana, Rajiv Gandhi announced instead a "postponement" of the transfer of Chandigarh. On May 23, 1986, Akali Dal members of parliament resigned in protest to form yet another splinter party aligned with the militants. Violence by Sikh extremists continued to escalate, and some groups again established themselves inside the Golden Temple. On November 30, 1986, the Khalistan Liberation Force49 claimed responsibility for the killing of 22 bus passengers near the city of Hoshiarpur in northern Punjab in the worst single massacre in five years. After that attack, a number of Sikh leaders were arrested and held under the provisions of the National Security Act, and parts of Punjab were declared "disturbed areas" in which the security forces, including the army, were granted increased powers to shoot to kill. Chief Minister Barnala's dependence on the support of the central government cost him the confidence of the powerful Sikh religious leaders, who eventually excommunicated him. The excommunication signalled the collapse of Barnala's administration, and on May 11, 1987, Barnala was removed from office by the central government.50 In Delhi, nearly the entire opposition in the parliament walked out to protest the central government's failure to consult with them before taking action. On March 6, 1988, the central government dissolved the state assembly in Punjab. No date was set for new elections, and the state remained under president's rule. At around the same time, Parliament passed the 59th amendment to the constitution, providing that a state of emergency could be declared in Punjab whenever "internal disturbance" threatened "the integrity of India." The amendment also permitted the suspension of article 19 of the Indian constitution guaranteeing fundamental rights, including freedom of speech and association, and article 21, which guarantees that "no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law." Under the amendment, the right to habeas corpus would be suspended.51 49 The group was believed at that time to be the armed wing of the All-India Sikh Students Federation. 50 The state assembly, however, was not dissolved. The central government justified dismissal of the Barnala administration on the grounds that ministers within the state government had obstructed the efforts of the security forces to combat terrorism. The Akali Dal accused the central government of using the dismissal to gain a political advantage in the elections in the neighboring Hindu-majority state of Haryana. 51 During the Emergency (1975-77), the suspension of habeas corpus facilitated widespread abuses, including illegal detentions, prolonged detention without charge or trial, 27 and torture. That legacy prompted Parliament to pass the 44th amendment to the constitution, stipulating that the fundamental rights guaranteed under articles 20 and 21 of the constitution could not be suspended. The 59th amendment provided for the revocation of the 44th amendment in Punjab. 28 In May 1988, commandos of the Indian army National Security Guards (NSG) launched a major offensive against some 100 armed men who had again created a fortified stronghold within the Golden Temple. Afterwards, the government negotiated an agreement with the SGPC to ensure that the militants would not be permitted to take over the temple again. In response, SGPC leaders requested guarantees for the lives of SGPC members who would then be at risk of assassination. Several members of the SGPC were reportedly assigned armed guards, including the head priest of the Golden Temple and the general secretary and office secretary of the SGPC. All three were assassinated in August 1988.52 Meanwhile militant violence claimed the lives of 73 people killed by bombs hidden in gunny sacks in markets in New Delhi, Amritsar and other cities. In an attempt to reopen negotiations with the Akali parties before national elections later that year, in March 1989 the "Jodhpur detainees," several hundred prisoners detained after Operation Bluestar who had been held without trial, were released.53 52 Vipul Mudgal, "Set-Back for Moderates," India Today, August 15, 1988, p. 31; Shekhar Gupta and Vipul Mudgal, "The Problems Ahead," India Today, June 15, 1988, p. 46. 53 The detainees -- most of whom were temple employees and pilgrims -- were originally held under the National Security Act, then charged with "waging war" under the Terrorist Affected Areas Act. The trial began in January 1985, but was suspended six months later. Throughout their detention, the government produced no evidence to substantiate the charge of "waging war." See Amnesty International, India: The Need to Review Cases Against 324 Sikhs Held for More than Four Years in Jodhpur Jail, Rajasthan, September, 1988, AI Index: ASA 20/03/88. 29 The National Front victory in the November 1989 parliamentary elections raised new hopes for a political settlement to the Punjab crisis. The 59th amendment to the constitution was repealed, and Prime Minister V.P. Singh promised to establish special courts to try those charged in the 1984 massacre of Sikhs in New Delhi, which had become one of the most important demands of Sikh political leaders.54 By the time this report went to print, no additional convictions had been reported.55 Despite promises to hold elections for the state assembly, in March 1990 the parliament amended the constitution to allow for an unprecedented extension of 54 In April 1989, seven human rights organizations issued a joint statement in response to claims made by then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi about actions taken to prosecute those responsible for the killings. "Till now -- after four and a half years -- the prosecution agency of the Government has been able to obtain convictions in just one murder case involving six people, who have been awarded life imprisonment by the sessions court. In the other murder cases, the accused have been acquitted primarily because of lapses in police investigation.... While repudiating the Prime Minister's preposterous claims regarding the 1984 carnage, we reiterate hereby that ... even after four and a half years the government has refused to punish the guilty." See "Wild Claims Regarding the 1984 Massacre of the Sikhs," Lokayan, vol. 7, no. 2 (March-April 1989), pp. 75-79. 55 In fact, when investigators attempted to question Saajan Kumar, a leading member of the Congress (I) who had been identified as providing liquor and money to the rioters, they were attacked outside Kumar's home by a gang of thugs apparently hired for his protection. See Barbara Crossette, "In India's Debate, Converging Issues," New York Times, October 1, 1990. 30 president's rule in the state.56 In October, president's rule was again extended. In November, Prime Minister V.P. Singh's government fell and was replaced by a Janata Dal administration under Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar. A long-time opponent of Congress(I) politics in Punjab, Chandra Shekhar was seen as one of the few leaders who could negotiate a political agreement. However, the first months of his administration saw an upsurge in militant violence with at least 500 people killed in November and December alone. By the end of the year, nearly 4,000 people were reported killed -- the highest number for any year since the conflict began. Army commandos of the National Security Guards were deployed to supplement the police and paramilitary forces in Punjab. 56 Under the constitution, president's rule cannot be extended longer than two years before holding elections. The 64th amendment also changed the term for the extension of president's rule from one year to six months. 31 In March 1991, Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar's government fell, paving the way for parliamentary elections in May. Despite fierce opposition from Congress (I) leaders, elections for both the national and state assembly were scheduled to be held in Punjab on June 22, a month after the general vote. Following the assassination of Congress (I) leader Rajiv Gandhi on May 21,57 general elections were postponed until June 12 and 15. As this report went to press, more than 24 candidates in Punjab had been assassinated. With the election of a Congress (I) minority government under Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, the Punjab elections were canceled on June 21 and tentatively rescheduled for September 1991. 57 Although no group claimed responsibility for the assassination, the militant Sri Lankan Tamil separatist organization, the LTTE, was believed responsible. 32 III. LINES OF AUTHORITY AND THE APPLICABLE LAW The primary government forces operating in Punjab are the Punjab Police, the Punjab Armed Police and members of India's principal paramilitary forces, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and the Border Security Force (BSF).58 In 58 In Punjab, the BSF and CRPF routinely engage in conflict with militants. They have combat duties and are, in effect, acting in lieu of army soldiers to perform purely military functions. The Punjab Armed Police sometimes assist in these operations. Their jurisdiction is legally restricted to Punjab state; however, they occasionally engage in operations in Chandigarh, along with the Chandigarh police. These are generally search operations; genuine combat between these forces and militant groups is intermittent and far less concentrated than in Kashmir. Also unlike Kashmir, there is no ethnic divide between the security forces and the militants and local population, as most of the Punjab police are also Sikh. See James Clad, "Terrorism's Toll," Far Eastern Economic Review, October 11, 1990, p. 34. Created in 1939, the Central Reserve Police Force is the largest of the paramilitary forces, with 130,000 personnel stationed nationwide in 108 battalions. As of December 1990, three-fourths of the CRPF was concentrated in four states: Punjab (200 companies), Jammu and Kashmir (125), Assam (60), and Uttar Pradesh (49). See Manoj Mitta, "A MiniIndia Protecting India," Times of India, December 23, 1990. Other reports indicate that the 33 addition to these forces, a number of other security detachments have been deployed, including the Indian Tibetan Border Police, the Central Industrial Security Force, and the Railway Police Force. One army unit is permanently stationed in Punjab, and as of late 1990, additional army units were deployed in the border districts to supplement the police and paramilitary forces.59 number of CRPF was increased before the elections in June 1991. The Border Security Force, created in 1962, operates in Punjab, Kashmir, West Bengal and the entire northeastern border of India, including the states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Mizoram, Tripura and Meghalaya. 59 The Indian army was first deployed in 1984 to remove Bhindranwale's forces from the Golden Temple. Again in 1988, Black Cat army commandos laid siege to the Golden Temple, forcing the surrender of militant leaders inside. 34 The number of militant groups operating in Punjab, and their relative power, is not known. None of the armed Sikh groups controls territory. There are at least seven major groups, loosely organized under three Panthic Committees.60 There are also numerous factions and other groups which operate as armed gangs profiting by extortion and arms smuggling.61 The militant groups themselves continue to spawn factions and splinters, each espousing different objectives. The criminality factor is high; the police do not exaggerate when they speak of unemployed youngsters drawn less to ideology and more to easy money gained from kidnap ransoms.... Often ready to fight among themselves, the gangs pin their primary loyalties to locality and kin.62 Most of the militants, whether bands of a half dozen men or organizations of hundreds of armed men with identifiable commanders, engage in ambushes of government forces and hit-and-run attacks for which they rely on automatic weapons such as AK-47s and other small arms, and explosives. Some groups appear to engage principally in assassinations, and some have also laid mines. The larger organizations appear to have at least a rudimentary command structure and some capacity for coordinating a military strategy. It is difficult to gauge the support the militants command in the countryside. Observers note that in some areas of Punjab, particularly along the Pakistan border, "after 5:00 p.m. there is a parallel government," and residents in rural areas "lock themselves in their houses after the sun sets" because of the large scale movement of militants at that time.63 While it is clear that villagers may provide shelter in some cases, in others they have been forced to do so at gunpoint. As one Indian civil liberties group notes, 60 In Sikhism, the panth is the community of believers. 61 For a description of the militant organizations and their history, see chapter 5. 62 James Clad, "Terrorism's Toll," Far Eastern Economic Review, October 11, 1990, p. 34. 63 Interview with journalist in Amritsar, December 9, 1990. 35 Villagers ... remain under constant fear of the terrorists as well as the police. Almost all the persons interviewed by us told us that there was a "police-raj" ["rule"] during the day and the terrorists ruled in the night.... Being sandwiched between the two, that is, the terrorists and the police, they remain bewildered and demoralised.64 Unable to locate or identify the militants, government forces routinely respond to militant attacks by detaining young Sikh men in the vicinity, some of whom may be subsequently executed in reported encounters. In other cases, the security forces have retaliated against entire villages, assaulting and torturing civilians and conducting mass arrests. Since 1984, Punjab has been under direct rule from Delhi for all but the two years between 1986 and 1988. In the absence of an elected state government, the civil administration has been under the authority of the governor, a federal appointee. The security forces, with the exception of the state police, operate under the authority of the federal home minister.65 While technically answerable to the governor, in fact the police function as a parallel government, one that is arguably more powerful than the civil administration because of the increased powers it has been granted to fight the militants. This rivalry has led to friction. Shortly before he was transferred in December 1990, Governor Virendra Verma gave an interview to the New Delhi based Frontline magazine in which he commented on the split between the two levels of authority. The police have got the upper hand and so the villagers have several complaints of harassment by the lower police staff. I have suggested that ... the civil authorities in the districts should be more active to check the harassment of the public. If [the civil 64 Citizens for Democracy, "Violence in Punjab," August 9, 1989. 65 According to a report published in India Today in April 1990, the CRPF and the BSF are under the authority of the the director general of police for Punjab. See Kanwar Sandhu, "Tough Tack," India Today, April 30, 1990, p. 18. 36 administration] becomes effective then it can have some kind of control over the police and the harassment would stop.66 66 "The Administration is not Effective," (Interview with Punjab Governor Virendra Verma), Frontline, December 8-21, 1990, pp. 11-12. 37 Conflict between the police and the civil administration over policy has resulted in the replacement of three governors in the past three years,67 leaving the police less accountable than ever to any civil authority.68 At the same time, the security forces, particularly the police and the paramilitary forces, have been granted sweeping powers to stem the separatist movement, and have been granted 67 Since 1983, Punjab has had eight different governors and six different police chiefs. See Shekhar Gupta, "Dangerous Upsurge," India Today, December 31, 1990, p. 30. As one observer notes, "A major obstacle to normalcy remains the police resistance to any state administration beholden to militant influence. There are many policemen who fear a reckoning of accounts for past excesses. Others in the security forces are loathe to surrender their special powers." James Clad, "Terrorism's Toll," Far Eastern Economic Review, October 11, 1990, p. 34. 68 The rift between Governor Verma and Deputy General of Police K.P.S. Gill became apparent during a controversy in November 1990 over two incidents of police encounter killings. When Verma's home secretary recommended registering criminal cases against the police officials involved, Gill objected, stating that such action would "lead to demoralisation and insubordination in the police ranks." Kanwar Sandhu, "New Frictions," India Today, November 15, 1990. See also p. 53. In January, Verma was transferred to become governor of Himachal Pradesh and was replaced in Punjab by O.P. Malhotra, a former army general. Following the national assembly elections in June 1991, Governor Malhotra resigned. 38 protection from prosecution. These forces routinely engage in human rights abuses in the name of "fighting terrorism." The security troops, which are largely unchecked by civilian or judicial authority, respond to their challenge by resorting to excessive force.... Police and paramilitary officers argue that a crusade for accountability will only demoralize soldiers.69 The Indian authorities have rarely conducted investigations into abuses committed by the security forces; in the few cases in which security personnel have been disciplined, the penalties have been dismissals or transfers. 69 Steve Coll, "India's Security Forces Assume New Power as Role in Ending Conflicts Grows," Washington Post, December 2, 1990. One senior police officer Coll interviewed in Punjab told him, "The politicians put us in this mess.... The police are asked to perform as the army and as politicians. How is that possible?" P.K. Parekh, a lawyer and director of the International Institute of Human Rights in New Delhi, told Coll, "They [the politicians] give the job of governance to the security forces.... The danger is ... once the forces taste power, they may not be able to give it up." Ibid. 39 Police high-handedness obviously stems from the simple fact that they can get away with it. Take the Brahmpura incident in December 1986, when it was proved beyond doubt that a CRPF posse had used excessive force while searching a village and even molested a woman. Three CRPF jawans ("servicemen") were picked up for punishment. [One] was demoted two ranks for three years, two increments of a head constable were withheld for two years and the third was dealt with in the orderly room by the commandant.... There have, in fact, been about a dozen magisterial inquiries in which police officials have been indicted. All have been swept under the carpet.70 Even after the severe torture of two women in the custody of the police in Batala in 1989 made headlines in the Indian press and received attention abroad, the only action taken was that the senior superintendent of police responsible was transferred.71 Despite considerable evidence that abuses like those in Batala have become endemic to security operations in Punjab, the authorities in the state and in New Delhi have consistently justified even gross human rights violations as an acceptable cost of the conflict. The Applicable Law 70 Kanwar Sandhu, "Uniformed Brutality," India Today, September 30, 1989, p. 27. 71 As one journalist noted at the time, the authorities excused the superintendent's actions on the grounds that the victims were alleged to be militants. "It seems unlikely that aside from a transfer any disciplinary action will be taken.... Particularly as the Director General of Police K.P.S. Gill ... now says that they had definite information that the two women were planning acts of terrorism." Ibid. 40 The government of India, like other governments, is obliged to respect internationally recognized human rights and is responsible for violations of those rights committed by and attributable to its armed forces and paramilitary forces.72 Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions and customary international law govern the conduct of both government forces and armed insurgents in internal armed conflicts. Common Article 3 to the four Geneva Conventions provides: In the case of armed conflict not of an international character occurring in the territory of one of the High Contracting Parties, each Party to the conflict shall be bound to apply, as a minimum, the following provisions: (1) Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, color, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria. To this end, the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the abovementioned persons: (a) violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture; (b) taking of hostages; (c) outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; 72 The government of India has ratified the four Geneva Conventions. The principal government forces operating in Punjab, the Punjab police, the CRPF, the BSF and the Indian army are all entities of the central government in New Delhi. Army soldiers report, ultimately, to the minister of defense; the CRPF, BSF and other national paramilitary police forces report to the home minister. As such, the actions of these troops are governed by the international laws of war and international human rights law which bind the government of India. In the periods in which Punjab has been under president's rule and the state legislative assembly has not been functioning, the central government has ruled the state directly. 41 (d) the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples. (2) The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for. Common Article 3 applies when a situation of internal armed conflict objectively exists in the territory of a state party; it expressly binds all parties to the internal conflict including insurgents, although they do not have the legal capacity to sign the Geneva Conventions. In Punjab, the Indian government and all principal armed militant organizations are parties to the conflict. The obligation to apply Article 3 is absolute for all parties to the conflict and independent of the obligation of the other parties. Thus, the Indian government cannot excuse itself from complying with Article 3 on the grounds that the militants are violating Article 3, and vice versa. Finally, the government of India is obliged as well to comply with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to which it is a party. 42 IV. VIOLATIONS BY GOVERNMENT FORCES Government forces operating in Punjab, including members of the Punjab police, the federal paramilitary troops of the Central Reserve Police Force and the Border Security Force, and the Indian army have systematically violated international human rights law and the international laws of war protecting civilians in internal armed conflict. Among the most egregious of these violations have been the summary executions of large numbers of civilians and suspected militants. During its mission to Punjab in 1990, the Asia Watch delegation investigated many cases of such killings that had occurred in 1989 and 1990 in districts throughout the state. In most cases the victims were killed after first being detained in the custody of the police or the paramilitary forces. The killings were then reported by the authorities as having occurred in an encounter with the security forces. In some cases, the police have reportedly recruited and trained extrajudicial forces made up of civilians, some of whom have been selected because of their criminal records, and members of the police, to carry out these killings. Security legislation has facilitated such abuses by authorizing the security forces to shoot to kill and by subsequently protecting them from prosecution. The security forces in Punjab have also engaged in widespread disappearances. Persons reported to have disappeared have been first detained in the custody of the police or security forces; subsequent to the arrest, the authorities have denied that the person was ever in custody. Detainees are routinely subjected to torture in police stations, prisons and detention camps. Asia Watch interviewed dozens of former detainees whose testimony described a pattern of systematic torture by the security forces to coerce signed confessions or information about alleged militants and to impose summary punishment. Family members are frequently detained and tortured to reveal the whereabouts of relatives sought by the police. During house-to-house searches, security forces routinely assault and threaten civilians. In some cases, the male residents of entire villages have been beaten and otherwise assaulted. Methods of torture include electric shock, prolonged beatings with canes and leather straps, tying the victim's hands and suspending him or her from the ceiling, pulling the victim's legs far apart so as to cause great pain and internal 43 pelvic injury, and rotating a heavy wooden or metal roller over the thighs. Female detainees also have been raped. Security legislation has suspended previous safeguards against torture, including the requirement that all detainees be seen by a judicial authority within 24 hours of arrest.73 Also suspended are prohibitions against the use of confessions obtained under duress. Detainees are frequently held in incommunicado detention, which also increases the risk of torture. Thousands of persons are believed to be detained throughout Punjab in police stations, at federal police camps and in prisons outside the state. Many of those detained appear to have been arrested solely because they are assumed to be militant sympathizers. Others are detained as hostages because their relatives or associates are suspected militants or because they live near militant strongholds. In such cases, persons may be detained on charges of "harboring terrorists." The police deliberately obstruct efforts by family members and lawyers to locate detainees and produce them in court by transferring the detainees from police station to police station. Habeas corpus petitions often do not provide a remedy in such cases because the police routinely defy court orders or deny that the detainee is in their custody. The detainees rarely have access to lawyers, and some have been denied medical care. Lawyers attempting to represent detainees have been harassed 73 These safeguards are included in India's Code of Criminal Procedure. Section 56 provides, "A police officer making an arrest without warrant shall, without unnecessary delay and subject to the provisions herein contained as to bail, take or send the person arrested before a Magistrate having jurisdiction in the case, or before the officer in charge of the police station." Under section 58, "Officers in charge of police stations shall report to the District Magistrate ... the cases of all persons arrested without warrant...." section 57 provides, "No police officer shall detain in custody a person arrested without warrant for a longer period than under all the circumstances of the case is reasonable, and such period shall not, in the absence of a special order of a Magistrate under Section 167, exceed twentyfour hours exclusive of the time necessary for the journey from the place of arrest to the Magistrate's Court." 44 themselves and in some cases also detained by the security forces. Persons also have been detained for peacefully exercising their rights of freedom of speech and assembly. Finally, the government has harassed some Punjabi newspapers, in some cases shutting down those which have published press statements released by the militant groups. Extrajudicial Executions While there is no declared state of emergency74 in Punjab, it is clear that violence by militants has claimed hundreds of civilian lives and seriously threatens civil order. Nevertheless, the actions taken by the security forces to crush the militants have resulted in the arbitrary deprivation of life on a huge scale.75 Furthermore, Common Article 3 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions requires in times of internal armed conflict that persons "taking no active part in hostilities ... be treated humanely" and prohibits "violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds." Common Article 3 also bars executions carried out "without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court." No derogation from these rules is permitted. The evidence gathered by Asia Watch indicates that the Punjab police, the Central Reserve Police Force, the Border Security Force and the Indian army -- the principal government forces operating in Punjab76 -- have systematically violated fundamental norms of international human rights and humanitarian law, most commonly by summary execution of civilians and suspected militants. Although the authorities generally claim that those killed were shot in encounters with the security forces, in fact, many of those killed in such reported encounters are simply 74 The 59th amendment to the constitution granted the government the authority to declare a state of emergency in Punjab on the grounds that "the integrity of India" was threatened. That authority was never invoked, and in 1990, the amendment was repealed. The amendment had been condemned by opposition parties and civil liberties groups in India. 75 Under Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the government of India has the right to derogate from certain articles of the ICCPR only if it first files a notification with the United Nations. However, the Indian government has not filed any such notification, making any derogation illegal. Moreover, the ICCPR expressly prohibits derogation from the right to life under any circumstance. Thus, even during time of emergency, "[n]o one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life." Article 6, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 76 The paramilitary forces deployed in Punjab, the CRPF and the BSF have combat duties and sometimes conduct operations jointly with the Punjab police. 45 murdered. The summary execution of civilians and captured combatants without charge or trial constitutes an extremely grave violation of Common Article 3. This pattern of extrajudicial killings by security forces has been documented by international human rights organizations and civil liberties groups and journalists in India.77 Publicly the police officers will never admit this phenomenon of fake encounters; privately, some of them would admit it and justify it. There is no other way to deal with the situation, they would say. You cannot reform them, you cannot get them convicted and you cannot keep them in detention indefinitely.78 77 Ironically, adopting the language of the security forces, these groups frequently use the term "encounter killings." One group explains, "The encounter: A unique contribution of the police in India to the vocabulary of human rights ... it represents in most cases the taking into custody of an individual or a group, torture and subsequent murder. The death generally occurs as a result of brutal torture or a stage-managed extermination in an appropriate area. An official press release then elaborately outlines a confrontation, an encounter where the police claim to have fired in `self-defence.'" People's Union for Civil Liberties, "Murder by Encounter," [no date], in A.R.Desai, ed., Violation of Democratic Rights in India, (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1986), p. 457. See also Andhra Pradesh Civil Liberties Committee, "`Encounter' Killings in Andhra Pradesh -- The Post Emergency Period," [no date], in same publication; and Amnesty International, Political Killings by Governments, (AI Index: ACT 03/26/82), 1983. 78 Prem Kumar, "Encounters of a Different Kind," Indian Express, June 12, 1989

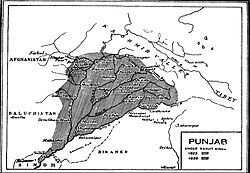

History of the Punjab

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Outline of South Asian history |

|---|

The name Punjab is a xenonym/exonym and the first known mention of the word Punjab is in the writings of Ibn Batūtā, who visited the region in the 14th century.[1]The term came into wider use in the second half of the 16th century, and was used in the book Tarikh-e-Sher Shah Suri (1580), which mentions the construction of a fort by "Sher Khan of Punjab". The first mentioning of the Sanskrit equivalent of 'Punjab', however, occurs in the great epic, the Mahabharata (pancha-nada 'country of five rivers'). The name is mentioned again in Ain-e-Akbari (part 1), written by Abul Fazal, who also mentions that the territory of Punjab was divided into two provinces, Lahore and Multan. Similarly in the second volume of Ain-e-Akbari, the title of a chapter includes the word Panjnad in it.[2] The Mughal KingJahangir also mentions the word Panjab in Tuzk-i-Janhageeri.[3] Punjab, derived from Persian and introduced by the Turkic conquerors of India,[4] literally means "five" (panj) "waters" (āb), i.e., the Land of Five Rivers, referring to the five rivers which go through it. It was because of this that it was made the granary of British India. Today, three of the rivers run exclusively in Punjab, Pakistan, while Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, India have the headwaters of the remaining two rivers, which eventually run into Pakistan.

Contents

[hide]Indus valley civilisation[edit]

Main article: Indus Valley Civilisation

Archaeological discoveries show that by about 3300 BCE the small communities in and around the Indus River basin had evolved and expanded giving rise to the Indus Valley Civilisation, one of the earliest in human history. At its height, it boasted large cities like Harrapa (near Sahiwal in West Punjab). The civilisation declined rapidly after the 19th century BCE.

Vedic Era[edit]

The Vedic period is characterised by Indo-Aryan culture associated with the texts ofVedas, sacred to Hindus, which were orally composed in Vedic Sanskrit. It embodies a literary record of the socio-cultural development of ancient Punjab (known asSapta Sindhu) and affords us a glimpse of the life of its people. Vedic society wastribal in character. A number of families constituted a grama, a number of gramas avis (clan) and a number of clans a Jana (tribe). The Janas, led by Rajans, were in constant intertribal warfare. From this warfare arose larger groupings of peoples ruled by great chieftains and kings. As a result, a new political philosophy of conquest and empire grew, which traced the origin of the state to the exigencies of war.

An important event of the Rigvedic era was the "Battle of Ten Kings" which was fought on the banks of the river Parusni (identified with the present-day river Ravi) between king Sudas of the Trtsu lineage of the Bharata clan on the one hand and a confederation of ten tribes on the other.[6] The ten tribes pitted against Sudas comprised five major the Purus, the Druhyus, the Anus, the Turvasas and the Yadus—and five minor ones, origin from the north-western and western frontiers of present-day Punjab—the Pakthas, the Alinas, the Bhalanas, the Visanins and the Sivas. King Sudas was supported by the Vedic Rishi Vasishtha, while his former Purohita the Rishi Viswamitra sided with the confederation of ten tribes.[7]

Punjab during Buddhist times[edit]

The Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya[8] mentions Gandhara and Kamboja among the sixteen great countries (Solas Mahajanapadas) which had evolved in/and aroundJambudvipa prior to Buddha's times. Pali literature further endorses that only Kamboja and Gandhara of the sixteen ancient political powers belonged to theUttarapatha or northern division of Jambudvipa but no precise boundaries for each have been explicitly specified. Gandhara and Kamboja are believed to have comprised the upper Indus regions and included Kashmir, eastern Afghanistan and most of the western Punjab which now forms part of Pakistan.[9] At times, the limits of Buddhist Gandhara had extended as far as Multan while those of Buddhist Kamboja comprised Rajauri/Poonch, Abhisara and Hazara as well as eastern Afghanistan including valleys of Swat and Kunar and Kapisa etc. Michael Witzel terms this region as forming parts of the Greater Punjab. Buddhist texts also mention that this northern region especially the Kamboja was renowned for its quality horses & horsemen and has been regularly mentioned as the home of horses.[10] However, Chulla-Niddesa, another ancient text of the Buddhist canon substitutes Yona for Gandhara and thus lists the Kamboja and the Yona as the only Mahajanapadas from Uttarapatha[11] This shows that Kamboja had included Gandhara at the time the Chulla-Niddesa list was written by Buddhists.

Pāṇinian and Kautiliyan Punjab[edit]

Pāṇini was a famous ancient Sanskrit grammarian born in Shalātura, identified with modern Lahur near Attock in the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan. One may infer from his work, the Ashtadhyayi, that the people of Greater Punjab lived prominently by the profession of arms. That text terms numerous clans as being "Ayudhajivin Samghas" or "Republics (oligarchies) that live by force of arms". Those living in the plains were called Vahika Samghas,[12] while those in the mountainous regions (including the north-east of present-day Afghanistan) were termed as Parvatiya Samghas(mountaineer republics).[13] According to an older opinion the Vahika Sanghas included prominently the Vrikas (possibly modern Virk Jatts), Damanis, confederation of six states known as Trigarta-shashthas, Yaudheyas (modern Joiya or JohiyaRajputs and some Kamboj), Parsus, Kekayas, Usinaras, Sibis[14] (possibly modern Sibia Jatts?), Kshudrakas, Malavas,Bhartas, and the Madraka clans,[15] while the other class, styled as Parvatiya Ayudhajivins, comprised among others partially the Trigartas, Darvas, the Gandharan clan of Hastayanas,[16] Niharas, Hamsamaragas, and the Kambojan clans ofAshvayanas[17] & Ashvakayanas,[18] Dharteyas (of the Dyrta town of the Ashvakayans), Apritas, Madhuwantas (all known as Rohitgiris), as well as the Daradas of the Chitral, Gilgit, etc. In addition, Pāṇini also refers to the Kshatriya monarchies of theKuru, Gandhara and Kamboja.[19] These Kshatriyas or warrior communities followed different forms of republican or oligarchic constitutions, as is attested to by Pāṇini's Ashtadhyayi.

The Arthashastra of Kautiliya, whose oldest layer may go back to the 4th century BCE also talks of several martial republics and specifically refers to the [Kshatriya Srenis (warrior-bands) of the Kambojas, Surastras and some other frontier tribes as belonging to varta-Shastr-opajivin class (i.e., living by the profession of arms and varta), while the Madraka, Malla, theKuru, etc., clans are called Raja-shabd-opajivins class (i.e., using the title of Raja).[20][21][22][23][24] Dr Arthur Coke Burnell observes: "In the West, there were the Kambojas and the Katas (Kathas) with a high reputation for courage and skill in war, the Saubhuties, the Yaudheyas, and the two federated peoples, the Sibis, the Malavas and the Kshudrakas, the most numerous and warlike of the Indian nations of the days".[25][26] Thus, it is seen that the heroicraditions cultivated in Vedicand Epic Age continued to the times of Pāṇini and Kautaliya. In fact, the entire region of Greater Punjab is known to have reeked with the martial people. History strongly witnesses that these Ayudhajivin clans had offered stiff resistance to theAchaemenid rulers in the 6th century, and later to the Macedonian invaders in the 4th century BCE.

According to History of Punjab: "There is no doubt that the Kambojas, Daradas, Kaikayas, Madras, Pauravas, Yaudheyas,Malavas, Saindhavas and Kurus had jointly contributed to the heroic tradition and composite culture of ancient Punjab".[27][28]

Empires[edit]

Achaemenid Empire[edit]

The western parts of ancient Gandhara, Kamboja and Taxila in North Punjab lay at the easternmost edge of the Achaemenid Empire.

The upper Indus region, comprising Gandhara and Kamboja, formed the 7th satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire, while the lower and middle Indus, comprising Sindhu (Sindh) and Sauvira, constituted the 20th satrapy, both part of the easternmost territories of the Achaemenids. They are reported to have contributed 170 and 360 talents of gold dust in annual tribute. It was said that the then Indian provinces of Sindhand Punjab were the richest satraps of the Persian empires generating vast revenues and even providing foot soldiers for the empire.

The ancient Greeks also had some knowledge of the area. Darius I appointed his Greek subject Scylax of Caryanda to explore theIndian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to Suez. Scylax provides an account of this voyage in his book Periplous.Hecataeus of Miletus (500 BCE) and Herodotus (483–431 BCE) also wrote about the Indus Satrapy of the Persians. In ancient Greek texts and maps, we find mention of the "mightiest river of all the world", called the Indos (Indus) of northern Indian subcontinent.

The presence of the Scythians in north-western India during the 4th century BCE was contemporary with that of the Indo-Greek Kingdoms there, and it seems they initially recognized and joined the power of the local Greek rulers.

Indo-Scythians[edit]

Maues first conquered Gandhara and Taxila around 80 BCE, but his kingdom disintegrated after his death. In the east, the Indian king Vikrama retook Ujjain from the Indo-Scythians, celebrating his victory by the creation of the Vikrama Era (starting 57 BCE). Indo-Greek kings again ruled after Maues, and prospered, as indicated by the profusion of coins from Kings Apollodotus II and Hippostratos. Not until Azes I, in 55 BCE, did the Indo-Scythians take final control of northwestern India, with his victory over Hippostratos.

Alexander's invasion[edit]

"The Kambhojas on the Indos (Indus), the Taksas of Taksila(Taxila), the Madras and Kathas (Kathaioi) on Akesines (Chenab), the Malla (Malloi) on the Hydraotis (Iravatior Ravi), the Tugras on the Hesidros (Sutlej) had formed important populations of the Punjab in the pre-Alexandrian age and stubbornly opposed Alexander on the Indus and, in spite of his victories on Hydaspes (Jhelum) and Sakala (Sangala,Sialkot), had finally led him and his soldiers to abandon his planned conquest of India and retire to Babylonia".[29]

After overrunning the Achaemenid Empire in 331 BCE, Alexander marched into present-day Afghanistan with an army of 50,000. His scribes do not record the names of the rulers of the Gandhara or Kamboja; rather, they locate a dozen small political units in those territories. This rules out the possibility of Gandhara and/or Kamboja] having been great kingdoms in the late 4th century BCE. In 326 BCE, most of the dozen-odd political units of the former Gandhara/Kamboja fell to Alexander's forces.

Greek historians refer to three warlike peoples, viz. the Astakenoi, theAspasioi[30] and the Assakenoi,[31][32] located in the northwest west of river Indus, whom Alexander had encountered during his campaign from Kapisi through Gandhara. The Aspasioi were cognate with the Assakenoi and were merely a western branch of them.[27][33][34] Both Aspasioi and Assakenoi were a brave peoples.[35] Alexander had personally directed his operations against these hardy mountaineers who offered him stubborn resistance in all of their mountainous strongholds. The Greek names Aspasioi and Asssakenoi derive from Sanskrit Ashva (or Persian Aspa). They appear as Ashvayanas andAshvakayanas in Pāṇini's Ashtadhyayi[36][37] and Ashvakas in the Puranas. Since the Kambojas were famous for their excellent breed of horses as also for their expert cavalry skills,[38][39][40] hence, in popular parlance, they were also known as Ashvakas.[27][33][41][42][43][44][45] The Ashvayanas/Ashvakayanas and allied Saka clans[46] had fought the Macedonians to a man. At the worst of the war, even the Ashvakayana Kamboj women had taken up arms and fought the invaders side by side with their husbands, thus preferring "a glorious death to a life of dishonor.".[33][47]

Alexander then marched east to the Hydaspes, where Porus, ruler of the kingdom between the Hydaspes (Jhelum)nearBhera and the Akesines (Chenab) refused to submit to him. The two armies fought the Battle of the Hydaspes River outside the town of Nikaia (near the modern city of Jhelum) and Poros became Alexander's satrap. Alexander's army crossed the Hydraotis and marched east to the Hyphases (Beas). However, Alexander's troops refused to face the vastly superior imperial army of Magadh Empire, Persoi refused to go beyond the Hyphases (Beas) River near modern-day Jalandhar. The Battle with Porus depressed the spirits of the Macedonians, as too many valiant comrades died helplessly by Porus' war elephants, and made them very unwilling to advance farther into India. Moreover, when they learned that a vastly superior imperial army of Magadh, Gangaridai and Prasii are waiting for the Greeks, all the generals of Alexander refused to meet them for fear of annihilation. Therefore, Alexander had to return. He crossed the river and ordered to erect giant altars to mark the eastern most extent of his empire thus claiming the territory east of Beas as part of his conquests. He also set up a city named Alexandria nearby and left many Macedonian veterans there, he himself turned back and marched his army to the Jhelum and the Indus to the Arabian Sea, and sailing to Babylon.

Alexander left some forces along the Indus river region. In the Indus territory, he nominated his officer Peithon as a satrap, a position he would hold for the next ten years until 316 BCE, and in the Punjab he left Eudemus in charge of the army, at the side of the satraps Porus and Taxiles. Eudemus became ruler of the Punjab after their death. Both rulers returned to the West in 316 BCE with their armies, and Chandragupta Maurya established the Maurya Empire in India.

Maurya Empire[edit]

Main article: Maurya Empire

The portions of the Punjab that had been captured under Alexander were soon conquered by Chandragupta Maurya. The founder of the Mauryan Empire incorporated the rich provinces of the Punjab into his empire and fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus, when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus, including Southern Afghanistan while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants. The Sanskrit play Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jaina work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, sometimes identified with Porus.[48] This Himalayan alliance is thought to given Chandragupta a composite and powerful army made up of the Yavanas (Greeks), Kambojas, Shakas (Scythians), Kiratas, Parasikas (Iranic tribe) and Bahlikas(Bactrians).[49][50] The Punjab prospered under Mauryan rule for the next century. It became a Bactrian Greek (Indo-Greek) territory in 180 BCE following the collapse of Mauryan authority.

Indo-Greek kingdom[edit]

Main article: Indo-Greek kingdom

Alexander established two cities in the Punjab, where he settled people from his multi-national armies, which included a majority of Greeks. These Indo-Greek cities and their associated realms thrived long after Alexander's departure. After Alexander's death, the eastern portion of his empire (from present-day Syria to Punjab) was inherited bySeleucus I Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid dynasty. Seleucus is said to have reach a peace treaty with Chandragupta of the Maurya Empire, by giving control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to him upon intermarriage and 500 elephants, establishing the close links that would develop between India and Afghanistan.

This was followed by the ascendancy of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. The Bactrian king Demetrius I added the Punjab to his Kingdom in the early 2nd century BCE. Some of these early Indo-Greeks were Buddhists. The best known of the Indo-Greek kings was Menander I, known in India as Milinda, who established an independent kingdom centred at Taxila around 160 BCE. He later moved his capital to Sagala (modern Sialkot).

The Indo-Scythians were descended from the Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from southern Siberia to Punjab and Arachosia from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura.

Following the centuries of Parthian clashes with its arch rival, the Roman Empire, a local Parthian leader in South Asia, Gondophares, established the Indo-Parthian Kingdom in the 1st century CE. The kingdom was ruled from Taxila and covered much of modern southeast Afghanistan and Pakistan.[51] Christian writings claim that the Apostle Saint Thomas – an architect and skilled carpenter – had a long sojourn in the court of king Gondophares, had built a palace for the king at Taxila and had also ordained leaders for the Church before leaving for Indus Valley in a chariot, for sailing out to eventually reach Malabar Coast.

Kushan Empire[edit]

Main article: Kushan Empire

The Kushan kingdom was founded by King Heraios, and greatly expanded by his successor, Kujula Kadphises. Kadphises' son, Vima Takto conquered territory now in India, but lost much of the west of the kingdom to the Parthians. The fourth Kushan emperor, Kanishka I, (c. 127 CE) had a winter capital at Purushapura (Peshawar, Afghanistan) and a summer capital at Kapisa (Bagram). The kingdom linked the Indian Ocean maritime trade with the commerce of the Silk Roadthrough the Indus valley. At its height, the empire extended from the Aral Sea to northern India, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between China and Rome. Kanishka convened a great Buddhist council in Taxila, marking the start of the pantheistic Mahayana Buddhism and its schism with Nikaya Buddhism. The art and culture of Gandhara — the best known expressions of the interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures — also continued over several centuries, until the 5th centuryWhite Hun invasions of Scythia. The travelogues of Chinese pilgrims Fa Xian (337 – c. 422 CE) and Huen Tsang (602/603–664 CE) describe the famed Buddhist seminary at Taxila and the status of Buddhism in the region of Punjab in this period.

Indo-Parthian Kingdom[edit]

The Gondopharid dynasty and other Indo-Parthian rulers were a group of ancient kings from Central Asia, who ruled parts of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, during or slightly before the 1st century AD. For most of their history, the leading Gondopharid kings held Taxila (in the present Punjab province of Pakistan) as their residence, but during their last few years of existence the capital shifted between Kabul and Peshawar. These kings have traditionally been referred to as Indo-Parthians, as their coinage was often inspired by the Arsacid dynasty, but they probably belonged to a wider groups of Iranian tribes who lived east of Parthia proper, and there is no evidence that all the kings who assumed the titleGondophares, which means ”Holder of Glory”, were even related.

Gupta Empire[edit]

Main article: Gupta Empire

Gupta empire existed approximately from 320 to 600 CE and covered much of the Indian Subcontinent including Punjab.[53] Founded by Maharaja Sri-Gupta, the dynasty was the model of a classical civilisation[54] and was marked by extensive inventions and discoveries.[55]